Rebranding Mary Jane: The Gentrification of Cannabis Culture in Lingerie

Today's guest post is written by Kawai (she/her). Kawai is a writer and cartoonist based in Toronto. You can find her on Twitter @kawaishen.

Fleur du Mal "Papillon" Silk Ensemble

The last few years have seen major breakthroughs for cannabis activists in the US and Canada. In 2018, Canada legalized cannabis while in the US, some states have also legalized. More recently, in 2020, the American House of Representatives approved the decriminalization of marijuana at the federal level.

These changing laws for recreational use are also changing who we think of as a typical marijuana user. This is leading to new ways of marketing and representing cannabis which is now being promoted in industries like food and beverages, cosmetics and wellness, fashion, and even lingerie.

via the Luxury Meets Cannabis Instagram

Gentrification is often used to describe the cannabis industry today. It’s a term referring to spaces populated by racialized, marginalized, and criminalized people that are taken over by more privileged newcomers. As these spaces shift to meet the needs and interests of newer residents, original community members are often shut out from the benefits of these changes.

Today, it’s mostly white and male cannabis entrepreneurs who are profiting from the cannabis industry's growth. At the same time, thousands, including Black, Indigenous, and other racialized people disproportionately targeted by drug policing, remain incarcerated for non-violent cannabis related offenses.

On the consumer side, CBD products and luxury cannabis goods have shot up like, well, weeds. Cannabis companies are also turning to sleek, Instagram-friendly designs and a classed-up image of the drug to advertise to new users.

Yandy "I'd Hit That" Mesh Bra Set - $38.95

This rebranding attempts to erase cannabis stigma. Culturally, the drug has long been associated with crime, laziness, physical and sexual pleasure, counter-culture attitudes, and lower class, racialized bodies. Newer cannabis consumers may be drawn to weed’s revamped look to disassociate themselves from stereotyped medical users, potheads, and dealers, some of whom were the activists who made it possible to legally toke.

When looking at lingerie featuring cannabis today, we see rebranded designs are reflecting changes in what we think is acceptable when it comes to who consumes weed and how.

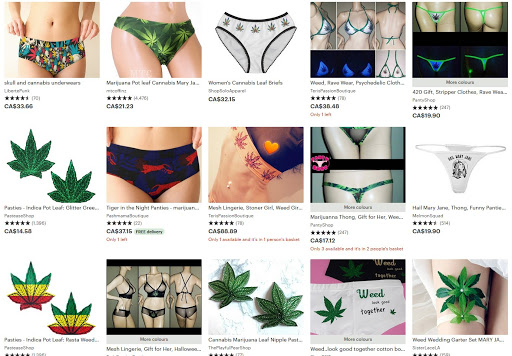

Author screenshot of an Etsy search for “cannabis lingerie”

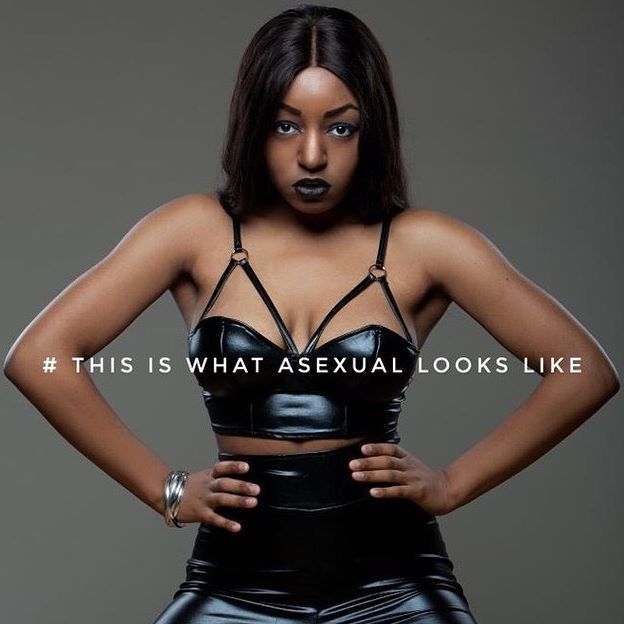

If you search for cannabis lingerie with Google or Etsy, the top hits reference stoner stereotypes and stoner-adjacent cultures from Rastafari to rave. Here we find lingerie showcasing giant leaves and doobies, saturated primary or neon colors, shiny textiles, and casual fonts declaring statements like “HIGH LIFE.”

Some pieces also sexualize women’s bodies with revealing “slingshot” micro cuts or phrases like “420 SLUT” or “I’d hit that.” This overt objectification offends common notions of what is respectable behaviour for women, so this style of cannabis lingerie may also strike some readers as low-class or vulgar.

More dedicated searching turns up gentrified designs from independent lingerie brands that try to soften or erase the drug's stigma while cashing in on its growing trendiness. Consider the following pieces that look like they belong more in a fashionable boutique than a head shop.

Solstice Intimates "Electric Lettuce"

The creative Electric Lettuce set is a part of a large cannabis-themed collection by Solstice Intimates, euphemistically named “Sweet Leaves”. Electric Lettuce is a slang term for cannabis and a playful reference for the in-crowd. The set unabashedly features weed leaves but strikes new ground with a unique design: a floaty, figure-obscuring top with pom-poms is paired with trendy, tap-pant style bottoms.

This irreverent style is shared with other “Sweet Leaves” pieces that blend distinctive Solstice designs with a 70s color palette and groovy use of velvet.

Recent photos from Solstice featuring models smoking joints and posing with pot plants, bongs, and rolling trays also use this hazy, sepia-tinted, retro aesthetic. In this way, Solstice safely features pot up-front by emphasizing a youthful nostalgia for the retro, white-and-middle-class-dominant hippie aspect of pot culture.

EmMeMa "Ditzy Cannabis"

EmMeMa Ditzy Cannabis Bralette - CA$82 and Briefs - CA$35

EmMeMa’s Ditzy Cannabis has a name that suggests a stoner approach, but its botanical print hardly brings to mind the stereotype of the couch-locked, chronic user. While the twee print of this casual bralette and brief set features cannabis leaves, the leaves are smaller in size and camouflaged by other botanicals. Here, cannabis is a Millennial trend, sold alongside other similar pieces with prints featuring cartoon cats, avocado halves, and Monstera leaves.

Thistle & Spire "Brooklyn Haze"

Thistle & Spire's Brooklyn Haze line has been featured on TLA before. This set presents us with a sincere effort to "class-up" cannabis. The product name is especially apt given Brooklyn's own gentrification.

Brooklyn Haze features the house's signature style of an exclusive pattern embroidered onto mesh tulle. The elegant embroidery departs from older cannabis designs by featuring teal thread and other flowers. The simple use of color, delicate hardware and specialty embroidery all impart a sense of chic polish. You might even fail to recognize the design as cannabis at first.

Brooklyn Haze offers an aspirational aesthetic, much like newer cannabis products being produced for the wellness and luxury markets. This kind of marketing has nothing to do with stoner culture and its cardinal sin of being baked and unproductive in a capitalist world. This new cannabis is about self-care and self-optimization.

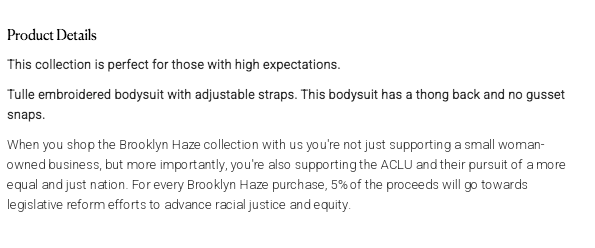

Screenshot of Brooklyn Haze pledge, via Thistle & Spire's website

On a related note, Thistle & Spire's response to the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 was to announce it would donate 5% of every Brooklyn Haze purchase to the American Civil Liberties Union. ACLU was chosen because of its work in criminal law reform and cannabis.

By reframing the purchasing of lingerie as a political action and a “promise to be better allies to Black and Brown communities,” Thistle & Spire (whose founders appear to be a white woman and an East Asian woman) rationalizes how it is profiting from cannabis when others remain incarcerated for it. More cynically, this could be read as a marketing exercise that trivializes the work of allyship and anti-oppression - a company paying a gentrification tax.

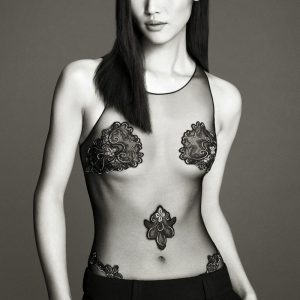

Fleur du Mal "Papillon"

Fleur du Mal Papillon Indigo smoking jacket - $495 (no longer available)

Fleur du Mal’s silk smoking jacket is available in Papillon, a botanical print featuring cannabis leaves. In addition to the jacket, Papillon silk is offered in matching “Bedroom to Boardroom” pants, a panty, a camisole, a robe, and other pieces. The product descriptions don't reference cannabis at all.

Fleur du Mal is the most expensive brand in this list and its product photos – glamorous shots of slender, polished women in upscale urban settings and pointy stilettos – make it clear that the wearer of these pieces is envisioned as conventionally beautiful and wealthy.

The matching blazer and pants set in particular suggest she belongs to a group that is not typically associated with a schedule-one drug like marijuana. This is a customer who can’t even acknowledge cannabis.

With Papillon, all associations with the marginalized and criminalized users of weed are removed from the plant, which itself is unnamed and reduced to visual decoration. For Fleur du Mal's wealthy consumers, cannabis is featured only to “jazz up” the clothes or make them more “edgy." It’s the end point of gentrification, the fashion equivalent of faux-heritage architecture pasted atop a shiny new condo build.

Where Does Cannabis Culture Go From Here?

Plus Size Leaf Print Swimsuit, via Shein - $15

A growing acceptance of cannabis doesn’t always result in a growing acceptance for all cannabis users, especially marginalized ones. Historically, privileged classes imposed prohibitions against cannabis use by working classes regardless of whether the use was recreational, medicinal, or spiritual.

American and Canadian law may be changing and prohibitions lifting, but these lingerie pieces show how the interests of the wealthy and powerful are still controlling how we view and use the plant.